Schedule-driven social adventure game?

Meet your weird neighbors simulator?

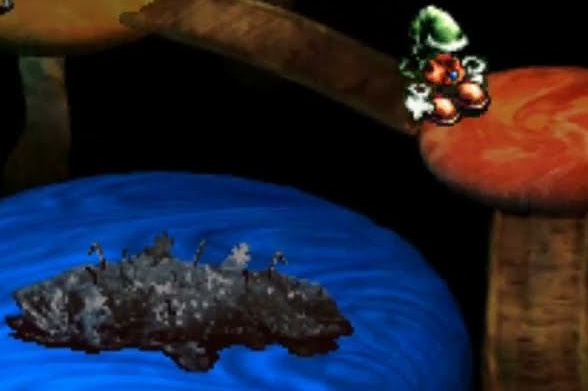

Moon-like?

I dis-like game genre names, but I can't get enough of being plopped into an unfamiliar world where myriad bizarre characters live their lives and time passes whether I like it or not. Love-De-Lic's Moon and Chulip would directly inspire recent indie gem 24 Killers and the upcoming Danchi Days, indicating a possible resurgence of the subgenre. Onion Games' own Stray Children promises more of that dreamy Moon goodness. And I'd be remiss not to honorably mention Majora's Mask's side quests and other recent indie gem Time Bandit as channelers of Love-De-Lic's design sensibilities.

I'm not just here to wax poetic about Moon, though. I think about the game constantly and still haven't pinned down what exactly it is that makes it so special. It's not simply the quirky characters and dialogue; I can talk about Earthbound all day, but it hits me in a different way than Moon. So this post is an exercise in, uh, figuring that out.

Ruminating......

The most concise way I can sum up the feeling is actually just as a broadening of the original "anti-RPG" branding: Love-De-Likes are anti-power fantasies staking their claim in a gaming culture, AAA and indie alike, obsessed with power fantasies. (Why else would "Role-Playing Game", about as generic a descriptor for a video game as possible, be implicitly understood to mean "Power Fantasy"?)

What all the aforementioned games share is not just a feeling, but a real presence of inevitability encoded in the game's mechanics. In an anti-power fantasy you do not and cannot shape the game world in your image. (Contrast with the superficially similar Animal Crossing.) Instead, the world shapes you.

All of these games enforce a rigid but cyclical time limit on your actions. Majora's Mask's oppressive 3-day cycle is the most (in)famous, stretching the limits of the N64's hardware (and many players' patience.) The side quests are the most obviously anti-power fantasy, but compared to other Zelda games even the main narrative skews this way, compelling the hero to beg four terrifying and terrifyingly unknowable τέρατα1 to save the world. Time Bandit's limitation is the most interesting to me, tracking hours-long, menial in-game tasks while the game isn't running, creating a slow-motion Sokoban to comment on how capitalism wastes all our time. Moon with its week-long cycle forces players to wait long periods to opposite effect by providing richly colored art and a phenomenal, customizable soundtrack to pass the time. The waiting in Moon, the downtime where I could do nothing but soak in the sensations of the game world, may be the single biggest factor in why I remember so much of it.

An anti-power fantasy asks what we can do to help others, improve the world in small ways, and improve ourselves when the possibility for wide-scale change is diminished or absent. To me it's the most real or immersive kind of game for this reason. Even in the real world, where long-term survival demands resistance and power-building, these games counteract the individualist chosen-hero narrative so common in, well, almost all mainstream culture. And even in the face of defeats and setbacks, these games remind us how to regroup and make change in the small ways we can. The small changes have to sustain, because even as it feels inevitable to get dragged backward, once in a blue Moon we'll take a step ahead.

1. Greek for 'marvel', 'divine sign', but also - 'monster'. Thanks to Sophia for helping me find this word <3↩